Key Takeaways:

- Understanding unconditioned stimuli basics

- Real-world examples of unconditioned responses

- Differences between conditioned and unconditioned stimuli

- Impact of timing on learned behavior

- Various forms of classical conditioning

Introduction to Unconditioned Stimulus

Let's dive into the fascinating world of unconditioned stimuli in psychology! These are the stimuli that naturally trigger a response without any prior learning. Think about how you react to a loud noise—you jump, right? That jump is an automatic response, not something you've learned. This automatic reaction is what we call an unconditioned response, and it's fascinating to see how these play out in various scenarios. Understanding unconditioned stimuli is like peeking into the fundamental wiring of our brains.

The Concept of Unconditioned Stimulus Explained

At its core, an unconditioned stimulus (US) is something that naturally and automatically elicits a response. In simple terms, it's a trigger that causes an innate reaction. For instance, when you touch something hot, you instantly withdraw your hand—no one had to teach you that! This reaction occurs because the hot surface is an unconditioned stimulus, and the withdrawal is an unconditioned response.

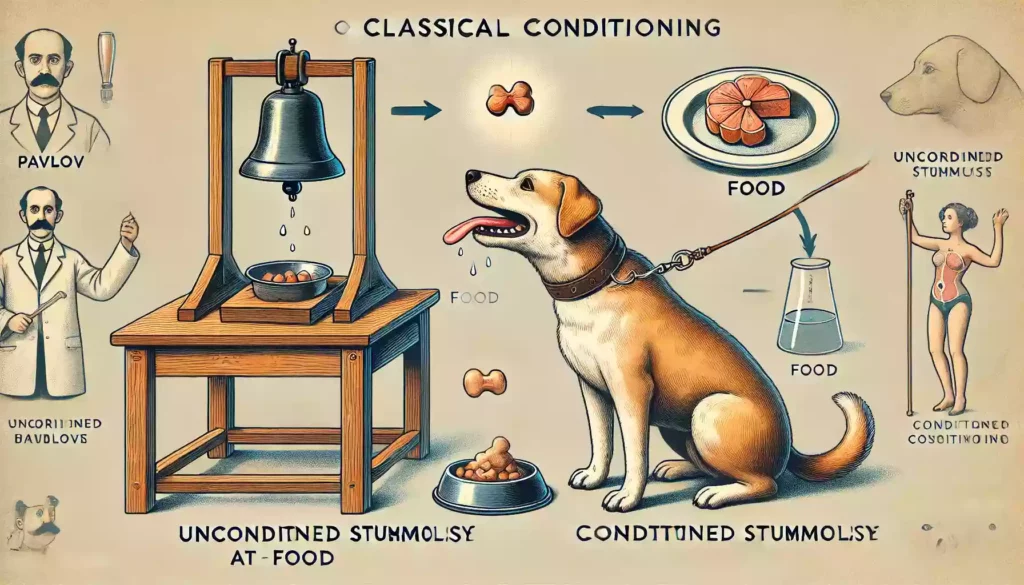

A classic example comes from the work of Ivan Pavlov, a Russian physiologist, who demonstrated how dogs would salivate upon seeing food. The food was the unconditioned stimulus, and the salivation was the unconditioned response. Pavlov's experiments laid the groundwork for understanding how associations are formed in our brains, leading to learned behaviors.

Unconditioned Stimulus in Pavlov's Experiment

One of the most iconic demonstrations of unconditioned stimuli comes from Pavlov's famous experiments. In these experiments, Pavlov presented food to dogs, which naturally caused them to salivate. Here, the food is the unconditioned stimulus (US), and the salivation is the unconditioned response (UR). What makes this study particularly interesting is how Pavlov introduced a neutral stimulus—a bell—before presenting the food. Initially, the bell did not cause any salivation; it was a neutral stimulus. However, after repeatedly pairing the bell with the presentation of food, the dogs began to salivate at the sound of the bell alone, even when no food was presented. This response to the bell is known as a conditioned response (CR), and the bell becomes a conditioned stimulus (CS). This experiment beautifully illustrates how an unconditioned stimulus can be used to condition a new response through association.

The Little Albert Experiment: A Case Study

The Little Albert experiment, conducted by John B. Watson and Rosalie Rayner, is another classic example that helps us understand the power of unconditioned stimuli. In this controversial study, a young child known as "Little Albert" was exposed to various stimuli, including a white rat, which initially did not frighten him. However, every time Little Albert reached for the rat, the researchers would produce a loud noise by striking a metal bar behind him. The loud noise, which naturally frightened Albert, served as the unconditioned stimulus (US), while his crying in response to the noise was the unconditioned response (UR).

Over time, Albert began to associate the white rat (which had been a neutral stimulus) with the loud noise. Eventually, he would cry just upon seeing the rat, even without the noise. The rat had become a conditioned stimulus (CS), and his fear response was now a conditioned response (CR). This experiment demonstrated not only the power of classical conditioning but also the ethical considerations in psychological research, as it involved inducing fear in a child.

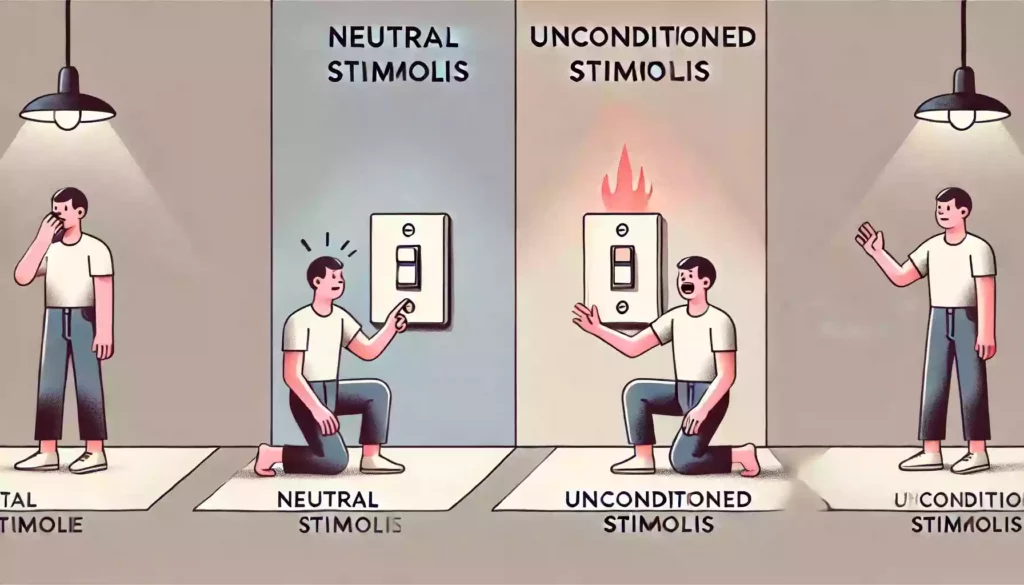

Differentiating Neutral and Unconditioned Stimuli

In psychology, it's crucial to distinguish between neutral and unconditioned stimuli, as they play different roles in our learning processes. A neutral stimulus (NS) is something that initially does not elicit any particular response or reaction. For example, a light switch, when first encountered, might not provoke any specific emotional or physical response—it's simply there. On the other hand, an unconditioned stimulus (US) is one that naturally triggers a reflexive reaction without any prior learning. A classic example is the automatic withdrawal of your hand when you touch something hot.

Understanding these distinctions helps us comprehend how certain responses are learned and conditioned over time. When a neutral stimulus is consistently paired with an unconditioned stimulus, it can eventually become a conditioned stimulus, eliciting a response similar to that of the unconditioned stimulus. This transformation is fundamental in classical conditioning and shapes much of our learned behavior.

Unconditioned vs. Conditioned Stimulus: Key Differences

Let's delve deeper into the differences between unconditioned and conditioned stimuli. An unconditioned stimulus (US) naturally and automatically triggers a response. For instance, the smell of food might make you feel hungry, or a loud noise might startle you. These responses are unlearned and occur without any previous conditioning.

A conditioned stimulus (CS), on the other hand, starts as a neutral stimulus but, through association with an unconditioned stimulus, begins to elicit a conditioned response. Consider Pavlov's bell, which initially had no effect on the dogs. However, after being paired repeatedly with the presentation of food (an unconditioned stimulus), the bell eventually triggered salivation (a conditioned response) even in the absence of food. This transition illustrates the process of learning through association, where the once-neutral stimulus takes on new meaning and influence.

The distinction between these stimuli is not just academic; it has practical implications for understanding behaviors, both in everyday life and therapeutic settings. By recognizing these differences, we can better understand how habits form, how phobias develop, and how therapeutic interventions can be designed to alter maladaptive responses.

The Timing of Learned Responses

Timing plays a pivotal role in the process of classical conditioning. The interval between the presentation of the conditioned stimulus (CS) and the unconditioned stimulus (US) can significantly influence the strength and speed of the conditioned response (CR). This interval is often referred to as the interstimulus interval (ISI), and it varies depending on the type of response being conditioned.

For example, in Pavlov's experiments, the bell (CS) was presented just before the food (US), creating a short delay known as forward conditioning. This timing allowed the dogs to anticipate the food, leading to a stronger salivary response. Conversely, if the CS and US are presented simultaneously or if the CS follows the US, the conditioning is less effective or may not occur at all. This concept is critical in understanding how associations are formed and maintained over time.

Timing isn't just a technical detail; it's a fundamental aspect of how we learn. In real-world scenarios, this can be seen in how habits are developed. If a positive reinforcement (like a reward) follows a desired behavior too long after the action, the association weakens. Therefore, the immediacy of the consequence is crucial in behavior modification, whether in training pets or teaching children.

Exploring Various Types of Classical Conditioning

Classical conditioning isn't a one-size-fits-all process. There are several types of classical conditioning, each with unique characteristics and implications. One common type is forward conditioning, as mentioned earlier, where the conditioned stimulus precedes the unconditioned stimulus. This is the most effective form and is commonly used in various learning scenarios.

Another type is backward conditioning, where the unconditioned stimulus is presented before the conditioned stimulus. This type is generally less effective because the subject may not associate the CS with the US, making the conditioned response weaker or nonexistent. Then there's trace conditioning, where the conditioned stimulus is presented and removed before the unconditioned stimulus is introduced. The trace interval, or the time between the removal of the CS and the presentation of the US, plays a critical role in the success of this conditioning method.

There's also simultaneous conditioning, where the CS and US are presented at the same time. While this can lead to learning, it's typically less effective than forward conditioning because the CS doesn't predict the US. Lastly, there's temporal conditioning, where the US is presented at regular time intervals, and the organism learns to anticipate the US based on the passage of time alone.

Understanding these various types of classical conditioning can help us appreciate the nuances of how we learn and adapt. It also highlights the complexity of our responses to the world around us, influenced by timing, order, and context. This knowledge is invaluable not just in theoretical psychology but also in practical applications like education, therapy, and personal growth.

Real-Life Examples of Unconditioned Stimuli

Unconditioned stimuli are all around us, influencing our behaviors in ways we often take for granted. A classic example is the reflexive action of pulling your hand away from a hot surface. The heat acts as an unconditioned stimulus, eliciting an automatic withdrawal response without any prior learning. This is an essential survival mechanism that protects us from harm.

Another common example is the sensation of hunger triggered by the sight or smell of food. When you walk past a bakery and catch a whiff of freshly baked bread, your stomach might start to growl, and you might even begin to salivate. This reaction occurs naturally and is not something you need to learn—it's an unconditioned response to the unconditioned stimulus of food aroma.

Unconditioned stimuli aren't limited to physical sensations. Emotional reactions can also be triggered. For instance, hearing a loud, sudden noise often causes a startle response, an unconditioned reaction that is automatic and instinctual. Similarly, experiencing a warm hug can trigger feelings of comfort and security, demonstrating the powerful and immediate impact of unconditioned stimuli on our emotional state.

The Psychological Impact of Unconditioned Stimuli

Unconditioned stimuli play a significant role in shaping our psychological landscape. They are at the core of many emotional and physiological reactions, influencing our behavior and well-being. The immediate, automatic responses they trigger can have profound effects, especially when these stimuli are associated with specific environments or experiences.

For example, the sight of a loved one can evoke an unconditioned response of joy and affection, creating a sense of emotional security and happiness. Conversely, unconditioned stimuli that are inherently unpleasant, such as the sound of a dentist's drill, can evoke anxiety or fear. These reactions can become deeply ingrained, affecting how we respond to similar stimuli in the future.

The psychological impact of unconditioned stimuli is not just about the immediate reaction but also about the long-term associations we form. These associations can influence our preferences, fears, and even our social behaviors. For instance, a positive unconditioned stimulus, like a smile from a stranger, can enhance our mood and encourage social interactions. On the other hand, negative stimuli can lead to avoidance behaviors or heightened stress responses.

Understanding the psychological impact of unconditioned stimuli helps us grasp how deeply they influence our lives, often beyond our conscious awareness. This knowledge is crucial in therapeutic settings, where identifying and modifying responses to unconditioned stimuli can lead to better mental health outcomes. Whether it's overcoming phobias, managing stress, or enhancing well-being, recognizing the power of unconditioned stimuli is a step toward greater self-awareness and control.

Concluding Thoughts on Unconditioned Stimulus

As we've explored, unconditioned stimuli are fundamental components of our psychological and physiological responses. These stimuli elicit natural, automatic reactions that do not require prior learning, shaping much of our daily behavior and emotional experiences. From the basic reflex of pulling away from a painful stimulus to the comfort of a familiar scent, unconditioned stimuli are intrinsic to how we navigate the world.

The concept of unconditioned stimuli is not just an academic curiosity; it's a window into understanding human behavior and emotions. By recognizing the power of these stimuli, we gain insight into why we react the way we do and how certain patterns of behavior are formed. This understanding is invaluable in various fields, from psychology and education to therapy and personal development.

Moreover, the study of unconditioned stimuli extends beyond the individual. It offers a glimpse into the shared human experience, highlighting the commonalities in how we respond to the world around us. Whether it's a spontaneous smile in response to kindness or an instinctual startle at a loud noise, these reactions connect us to others and to our environment in profound ways.

Unconditioned stimuli are more than just triggers of automatic responses; they are a key to unlocking the complexities of human nature. By understanding these basic yet powerful elements, we can better appreciate the intricacies of our minds and behaviors. This knowledge empowers us to make informed choices, manage our reactions, and ultimately lead more fulfilling lives.

Recommended Resources

- "Principles of Psychology" by William James - A foundational text that explores the psychological processes, including the concept of unconditioned stimuli.

- "Behaviorism" by John B. Watson - This book delves into the principles of behaviorism and classical conditioning, with insights into experiments like Little Albert.

- "Pavlov's Dogs and the Discovery of Classical Conditioning" by John Arena - A comprehensive look at Pavlov's experiments and their implications for psychology.

.thumb.jpg.2d93ce2472f26b01a1e185382ba0b64e.jpg)

Recommended Comments

There are no comments to display.

Create an account or sign in to comment

You need to be a member in order to leave a comment

Create an account

Sign up for a new account in our community. It's easy!

Register a new accountSign in

Already have an account? Sign in here.

Sign In Now